Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Annual Rate of Economic Growth" width="1251" height="819" />

Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Annual Rate of Economic Growth" width="1251" height="819" />On December 15, 2017, a House of Representatives and Senate Conference Committee released a unified version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. This followed passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act by the House of Representatives on November 16, 2017, and by the Senate on December 2, 2017. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would reform the individual income tax code by lowering tax rates on wages, investment, and business income; broadening the tax base; and simplifying the tax code. The plan would lower the corporate income tax rate to 21 percent and move the United States from a worldwide to a territorial system of taxation.

Our analysis[1] finds that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would reduce marginal tax rates on labor and investment. As a result, we estimate that the plan would increase long-run GDP by 1.7 percent. The larger economy would translate into 1.5 percent higher wages and result in an additional 339,000 full-time equivalent jobs. Due to the larger economy and the broader tax base The tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. , the plan would generate $600 billion in additional permanent revenue over the next decade on a dynamic basis. Overall, the plan would decrease federal revenues by $1.47 trillion on a static basis and by $448 billion on a dynamic basis. The remaining difference is explained by temporary dynamic revenue growth from the bill’s numerous expiring provisions.

These results differ from our previous analysis of the original House version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and the original Senate version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, due to the multitude of changes during each chamber’s markup process and agreements made during the conference committee.

| Single Filer | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Law | Tax Cuts and Jobs Act | ||

| 10% | $0-$9,525 | 10% | $0-$9,525 |

| 15% | $9,525-$38,700 | 12% | $9,525-$38,700 |

| 25% | $38,700-$93,700 | 22% | $38,700-$82,500 |

| 28% | $93,700-$195,450 | 24% | $82,500-$157,500 |

| 33% | $195,450-$424,950 | 32% | $157,500-$200,000 |

| 35% | $424,950-$426,700 | 35% | $200,000-$500,000 |

| 39.6% | $426,700+ | 37% | $500,000+ |

| Married Filing Jointly | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Law | Tax Cuts and Jobs Act | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Note: The Head of Household filing status is retained, with a separate bracket schedule. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10% | $0-$19,050 | 10% | $0-$19,050 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15% | $19,050-$77,400 | 12% | $19,050-$77,400 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25% | $77,400-$156,150 | 22% | $77,400-$165,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28% | $156,150-$237,950 | 24% | $165,000-$315,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33% | $237,950-$424,950 | 32% | $315,000-$400,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 35% | $424,950-$480,050 | 35% | $400,000-$600,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 39.60% | $480,050+ | 37% | $600,000+ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

According to the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth Model, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would increase the long-run size of the U.S. economy by 1.7 percent (Table 3). The larger economy would result in 1.5 percent higher wages and a 4.8 percent larger capital stock. The plan would also result in 339,000 additional full-time equivalent jobs.

The larger economy and higher wages are due chiefly to the significantly lower cost of capital under the proposal, which reduces the corporate income tax rate and accelerates expensing of capital investment for short-lived assets.

Change in long-run GDP

Change in long-run capital stock

Change in long-run wage rate

Change in long-run full-time equivalent jobs

The long-run economic changes are generated by the corporate income tax rate cut. Table 4 below isolates the economic impact of this key provision that increases long-run economic growth.

Lower the corporate income tax rate to 21 percent.

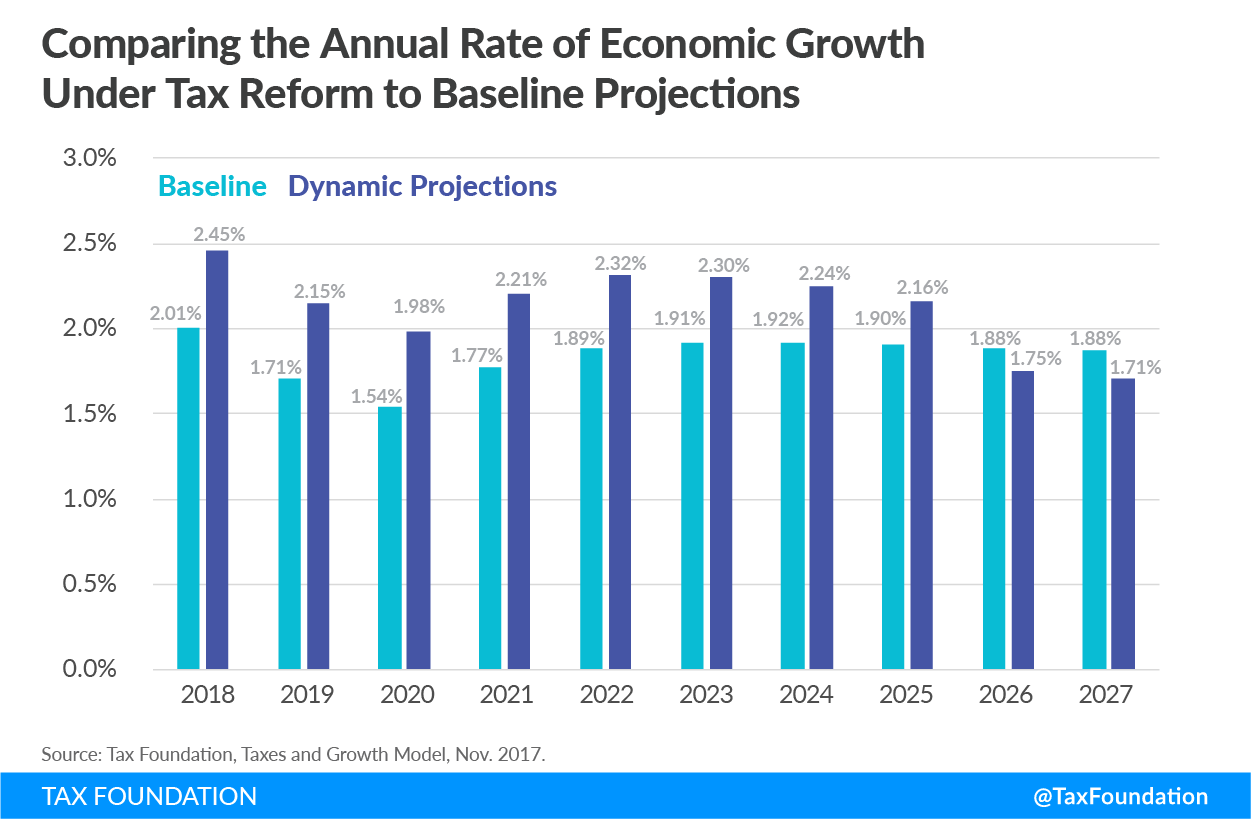

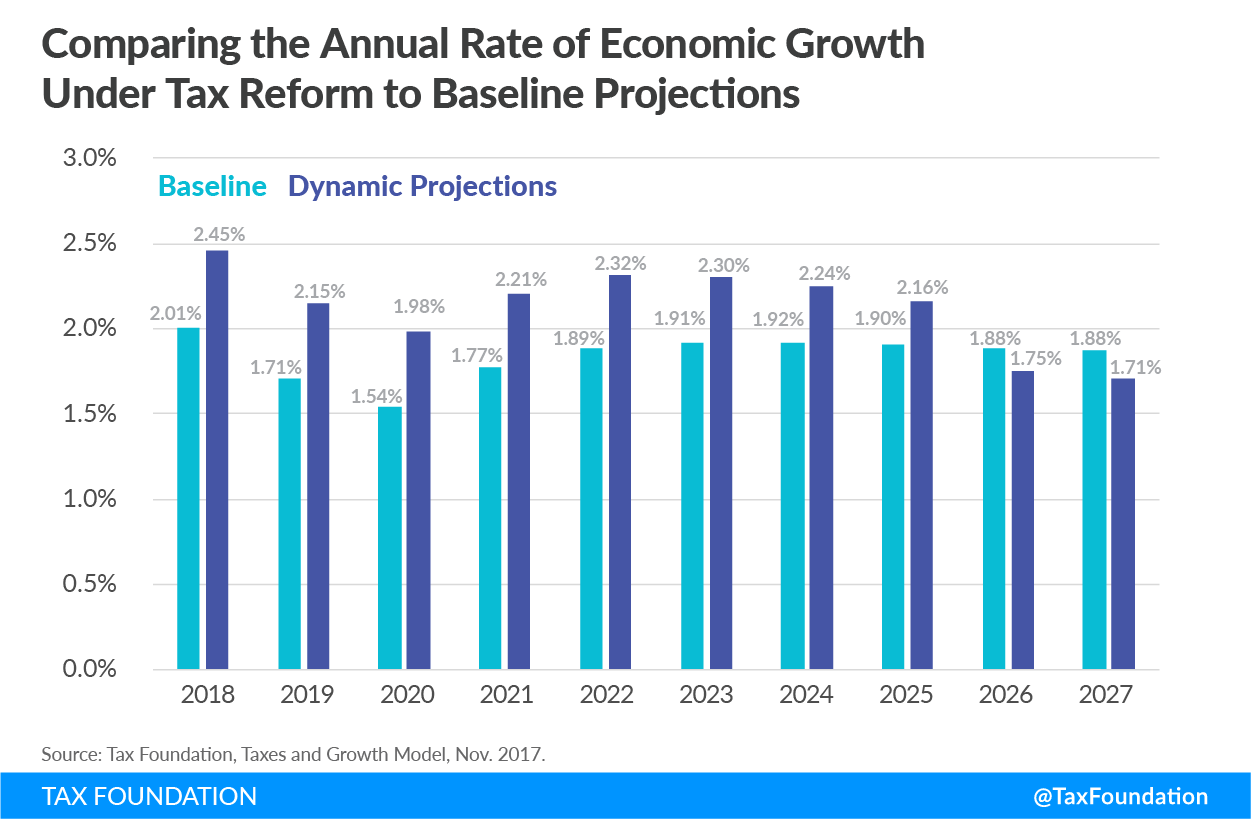

The growth of GDP under this plan, however, is not linear. In 2018, the first year of this tax plan, growth is projected to jump 0.44 percent above the current baseline projection as firms take advantage of the full and immediate expensing of equipment and the lower corporate income tax rate. These provisions encourage capital investment.

The initial spike in growth is reduced later during the decade, however, when growth falls slightly below the baseline. This is due to the temporary nature of many of these provisions. Economic growth is borrowed from the future, but the plan, in aggregate, still increases economic growth over the long run. The figure below illustrates this phenomenon.

Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Annual Rate of Economic Growth" width="1251" height="819" />

Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Annual Rate of Economic Growth" width="1251" height="819" />Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Over the next decade, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would increase GDP by 2.86 percent over the current baseline forecasts, or an average of 0.29 percent per year. This means an increase of total GDP of approximately $5 trillion over the next decade, well exceeding the revenue lost by the plan.

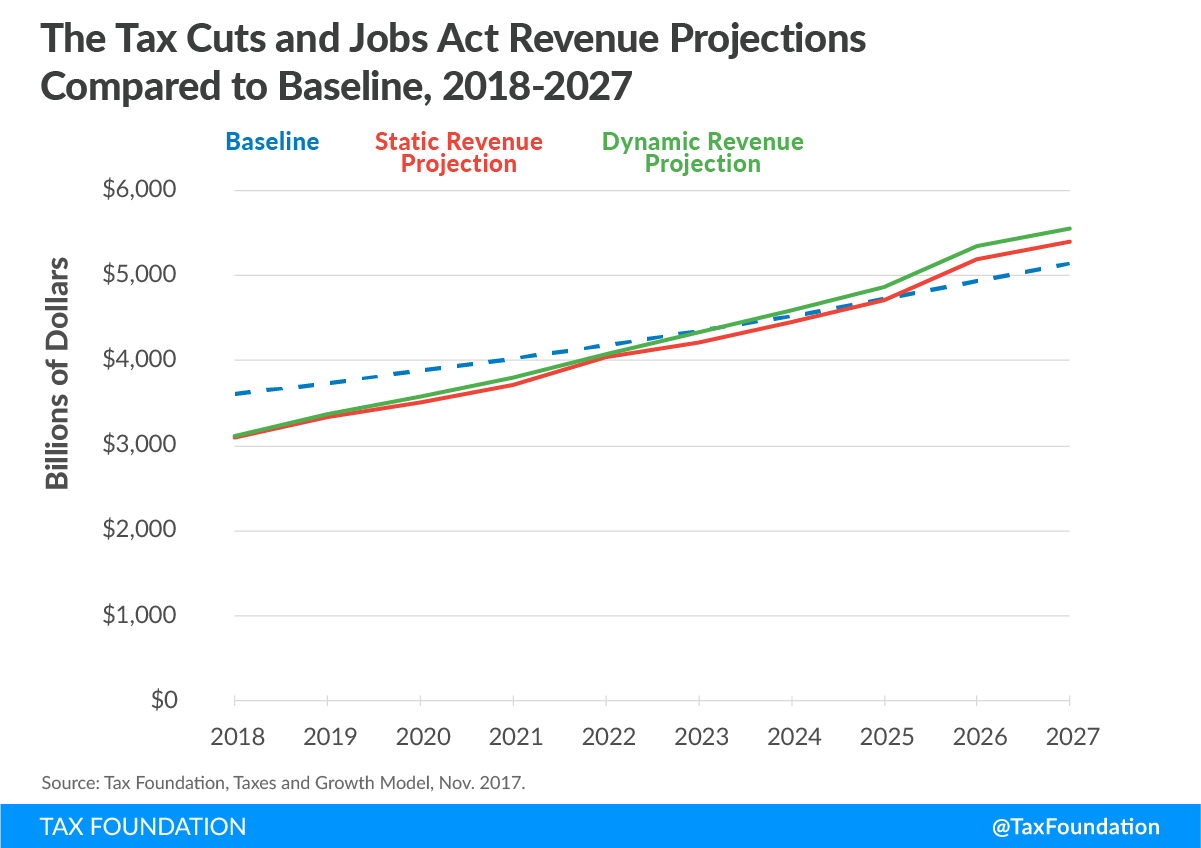

If fully implemented, the proposal would reduce federal revenue by $1.47 trillion over the next decade on a static basis (Figure 2) using a current law baseline. The plan would reduce individual income tax revenue, excluding the changes for noncorporate business tax filers, by $1.1 trillion over the next decade. Tax revenue from the corporate income tax and from taxation of pass-through business income would fall by $617 billion. The remainder of the revenue loss would be due to the doubling of the estate tax exemption, resulting in a revenue loss of $72 billion.

On a dynamic basis, this plan would generate an additional $600 billion in revenues, reducing the cost of the plan over the next decade. The larger economy would boost wages and thus broaden both the income and payroll tax base. As a result, the federal government would see a smaller revenue loss from personal tax changes, of $494 billion. The reduction in tax revenue from business changes would also be smaller on a dynamic basis, at $565 billion. The corporate tax revenue loss would be most significant in the short term because of the temporary expensing provision for short-lived assets, which would encourage more investment and result in businesses taking larger deductions for capital investments in the first five years of the plan.

The figure below compares static and dynamic revenue collection to the current law baseline. By the end of the decade, dynamic revenues have exceeded the baseline. In fact, dynamic revenues exceed the current law baseline in 2023, when the temporary expensing provisions expire, as the costs of the plan drop.

Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Revenue Projections" width="1201" height="848" />

Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Revenue Projections" width="1201" height="848" />

By 2024, dynamic revenue projections are back above the baseline projections, meaning that federal revenues would actually increase in those years when accounting for economic growth. In 2026, static revenue projections are also above the baseline projections, largely due to the expiration of many individual provisions. These results, however, should not be interpreted to mean that these tax changes are self-financing. Instead, they illustrate that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act includes a number of revenue offsets to reduce the overall cost of the tax rate cuts included in the plan.

The first large set of base broadeners is the elimination of a number of credits and deductions for individuals. Notably, the state and local tax deduction would be limited to a maximum deduction of $10,000 for income, sales, and property taxes (except as they are related to business activity), and the mortgage interest deduction would be limited to the first $750,000 in principal value. The plan would also limit a number of deductions. These provisions would raise $640 billion over the next decade.

On the business side, the bill includes several base broadeners. It would limit the net interest deduction to 30 percent of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) for four years, and 30 percent of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) thereafter, including for already originated loans. It would also limit or eliminate a number of business tax expenditures, such as the domestic production activities (section 199) deduction, the orphan drug credit, and the deduction for entertainment expenses. Repealing and limiting many of these expenditures would generate $1.0 trillion in revenue.

The largest source of revenue loss in the first decade would be the individual and corporate rate cuts. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would retain the current seven individual income tax brackets, but would modify both their widths and tax rates. The top marginal tax rate The marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. would fall from 39.6 percent under current law to 37 percent, with many other rates decreasing as well. The individual income tax rate changes, however, are temporary until December 31, 2025. This reduces the cost of the changes over the 10-year budget window, as they are only in effect for eight of the 10 years. These changes would reduce revenues by $1.9 trillion. The corporate income tax rate would fall from 35 percent to 21 percent on January 1, 2018, reducing revenues by $1.4 trillion. The plan would also provide many pass-through businesses with a 20 percent deduction for pass-through business A pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. income. Specified service business would be ineligible, except for households with taxable income below $157,500 for single filers and $315,000 for married filers. This provision reduces revenue by $289 billion. The pass-through provisions expire at the end of 2025.

Table 5 summarizes the revenue impacts, both static and dynamic, of each of the major provisions.

Individual

Raise the alternative minimum tax exemption and the exemption phaseout threshold

Adjust individual income tax rates and thresholds, creating seven rates of 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, and 37%.

Increase the standard deduction to $12,000/$18,000/$24,000.

Repeal personal exemptions.

Increase the child tax credit amount to $2,000. Initially, only the first $1,400 of the credit is refundable. Decrease the phase-in threshold of the refundable portion of the credit to $2,500. Increase the phaseout threshold of the credit to $400,000 for married filers and $200,000 for other filers. Create a $500 nonrefundable credit for non-child dependents.

Cap the deduction for state and local taxes paid at $10,000. Cap the mortgage interest deduction at $750,000 of acquisition debt. Eliminate several other deductions. Limit the casualty loss deduction, and modify limits on the charitable deduction. Repeal the Pease limitation on itemized deductions.

Modify or repeal other personal deductions, credits, and exclusions.

Index bracket thresholds, the standard deduction amount, the refundable portion of the child tax credit, and other provisions to chained CPI (economic effect not modeled).

Individual subtotal

Business

Lower the corporate income tax rate to 21 percent, effective 1/1/2018

Create a 20% deduction for pass-through business income. The deduction is limited for households with more than $157,500/$315,000 that earn income from service businesses; these households are also subject to a test based on each business’s W-2 wages.

Increase the limit for §179 expensing. Require R&D expenses to be amortized after 2021. Limit interest deductibility to 30% of EBITDA until 2021 and 30% of EBIT afterward. Limit NOL deductions to 80% of taxable income. Allow 100% expensing for assets other than structures for five years, phased out over successive years.

Modify or repeal other business deductions, credits, and other provisions.

Enact a deemed repatriation of foreign-source income at a rate of 15.5% for liquid assets and 8% for illiquid assets.

Modify several aspects of the tax treatment of foreign-source income.

Business subtotal